THEATER REVIEW; Water World: Love of Plumbing

The New York Times

By Peter MarksA $5 billion water tunnel stretching 64 miles: they said it couldn't be done. No, not building one; writing a compelling show about one. The topic does sound better suited to a convention of hydrologists than to an audience of New Yorkers with the usual level of curiosity about urban plumbing. (In other words, zzzzzzz.) But against all odds, Marty Pottenger establishes a city water-delivery system as the backdrop for an often lyrical show that speaks with intimate knowledge, and yes, even love, about holes in the ground and the people who drill them.

"City Water Tunnel No. 3," a presentation at the Judith Anderson Theater written and performed by Ms. Pottenger, a carpenter who spent 20 years in the building trades, gives new meaning to "underground theater."

Embroidered by video scenes of the tunnel in progress and the actress's compassionate impressions of laborers, engineers and bureaucrats, the performance piece consists of vignettes illuminating aspects of the vast project, begun more than 20 years ago and not scheduled for completion for 25 more years: the construction of a third tunnel to carry billions of gallons of drinking water to the city from upstate reservoirs. The challenge here, of course, is to make the prosaic poetic. The construction job -- "the largest nondefense public works project in the Western Hemisphere," the narrator tells us -- already has scale.

What it needs is personality, which Ms. Pottenger supplies, in her own voice and the voices of the workers whose verbatim stories she tells. The big pipe, or rather, "this beautiful concrete cylinder," as Ms. Pottenger calls it, is a conveyance for a portrait of contemporary folkways; it's as if the actress were paddling here and there along a cement Mississippi. On a stage designed to look like a construction site, she offers a primer on tunneling, from the floating of the bonds to the opening of the valves. Safety is essential on such a project -- 24 people have died building this one -- and so is the omnipresent pot of coffee. Her characters tell New York stories, immigrant stories, in the accents of Poland, Russia, Ireland and Jamaica.

The approach is a blending of Studs Terkel, Anna Deavere Smith and Pete Seeger, in which Ms. Pottenger seeks to bind the people building the pipe to the people it is meant to serve. As Tony, one of the workers Ms. Pottenger impersonates, puts it, without the project New York might not survive, because there would be "no drinkin', no floatin', no flushin', no soapin' and no scrubbin'."

Ms. Pottenger appears to have a heart as big as the tunnel. This has its advantages and drawbacks: while her soft spot for each and every subject is apparent, it's hard to believe a task this complex could be accomplished with so little rancor. She also hints at an on-the-job sexism that as a woman in the construction business she must have experienced firsthand. You do, at times, get the feeling that she's holding back something. Maybe that's for another show.

Written and performed by Marty Pottenger; directed by Jayne Austin-Williams; Steve Elson, composer; Tony Giovannetti, lighting and technical director; sound by Mio Morales; Arden Kirkland, costume consultant. Presented by the Working Theater, Robert Arcaro, artistic director; Mark Plesent, producing director. At the Judith Anderson Theater, 424 West 42d Street, Clinton.

Published: 06 - 09 - 1998 , Late Edition - Final , Section E , Column 4 , Page 5

City Water Tunnel #3: Groundbreaking Performance

The Austin Chronicle

By Wayne Alan BrennerMarty Pottenger, all by herself, performing City Water Tunnel #3 as part of the Rude Mechanicals' Throws Like A Girl series, is not going to knock your socks off. You're not, as you're watching her, as you're listening to her, going to think: "Damn, this woman is an absolutely riveting presence, a polished theatre professional whose every move is an exercise in perfection."

But you don't need to think that: You're going to be too busy thinking about other things. About what it's like to work on the largest non-defense public works project in the Western Hemisphere. About what it's like to spend your days wrangling hundreds of pounds of dynamite, hundreds of tons of rock and dirt and mud (muck, they call it), earth-boring machines, drills the size of minivans, water pipes and their attendant valves, and all the kinds of equipment and procedures necessary to precisely compromise our planet's thick crust. Even about what it's like to die violently, doing this.

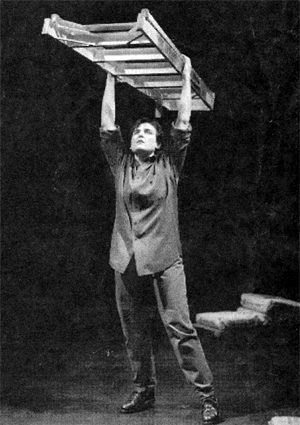

Pottenger brings this little-seen world to the Off Center stage, using relevant job-site props (ladders, bags of cement, hardhats, a water level), a video highlighting aspects of the actual project, and a series of monologues to better illustrate the subject and her experience researching it. It's one hell of a story, a multifaceted glimpse into an enormous subterranean endeavor and all the pain and suffering and joy that goes into it while the rest of us perform our (usually) more pedestrian day jobs above ground.

We hear -- through Pottenger's impersonations -- the voices of sandhogs talking about union dynasties, of geologists waxing philosophical on the peregrinations of tectonic plates, of ordinary folk whose hometowns have been purposefully and permanently flooded to provide reservoir space. And we hear Pottenger, too, in her own voice, speaking of the barriers she had to overcome in documenting all the activity and of the sometimes reluctant kinship she felt with the workers involved. She stops the flow of narrative at times to demonstrate the use of a water level or to perform a sort of interpretive dance with a utility ladder; and she does this in such a way that it's disarming. There's no Disneyfied slickness of presentation going on here: There's a woman, a particular woman, Marty Pottenger, and as best as she can, she's sharing what she's learned and she's sharing her feelings about it. As she brings us tales of the human side of heavy demolition and construction -- many of them scraped into the walls of auditory memory by the literally earth-shaking sound design of Mio Morales -- she's also bringing us a very human performance, becoming no less a character than those colorful individuals she's interviewed.

If the Department of Environmental Protection hired someone to provide this wealth of information, that someone couldn't do a better job -- if only because the resultant show would be infused with the sort of rah-rah spin-doctory sales job that taints most corporate PR. Here, we get the truth, as plain and raw as the earth that's being tunneled, as bright and ragged as the people tunneling. We understand, finally, the deeper need for labor; and we understand it through this labor of love.

Published: March 8, 2002